Looking at You, a new opera—with music by Kamala Sankaram, libretto by Rob Handel and developed with and directed by Kristin Marting—premiered this fall to great anticipation and acclaim. The opera tells the story of employees at a tech company grappling with issues of privacy, loyalty and the impact of their work on the world at large. EiO Co-Founder, Jason Cady talked with Kamala and Rob to learn more about their perspectives about the piece and how they worked together.

________________________________________________________________________

Jason: First, could you just tell us what Looking At You is about?

Rob: It’s about a coder who gets her dream job as chief engineer at a big company. You know, think Google or Facebook. And just as she’s enjoying this job that her entire life’s work has led to, a story breaks on the news that her Ex has become a whistleblower and revealed a plot by 13 governments to spy on on their own citizens and to keep their audio recordings and the messages of where their GPS went and all the things that the surveillance capitalism system is now keeping track of on us. And because this person was her Ex, she’s involved in the manhunt for him, as he tries to find a safe place somewhere after having blown the whistle on all these governments.

Jason: And it references Casablanca, right? Like the title comes from “Here’s looking at you, kid?”

Rob: Casablanca has more memorable lines that everyone knows than any other movie. One of them near the end is Humphrey Bogart says to Ingrid Bergman, “This thing’s bigger than both of us,” about the threat to civilization by the Nazis. And that really is the core idea that connected the themes in our show, because it’s about characters who have to make a decision between, their feelings and the threats to freedom that surveillance capitalism represents. The parallel is that if any particular group of people can be persecuted using these tools, then anyone can, and no one is really free.

Jason: Are there any musical connections with Casablanca, like quotations from the song As Time Goes By?

Kamala: There are no exact quotations, but the approach to the music is driven by the soundtracks of film noir. So that’s where the saxophone trio came from—trying to capture what those films sounded like. It’s a kind of jazz that’s supposed to signify urbanity and modernity, but of course the urbanity and modernity of the ‘40s and ‘50s.

Jason: It’s a unique instrumentation, so I’m guessing your other choices were deliberate for this piece. You have piano, like “Sam the piano player” in Casablanca, and the electronics convey the idea of technology?

Kamala: Because the piece is so much about our real lives versus our lives online, I felt like the music had to mirror that. So we go back and forth between these EDM-inspired sections that are really about the tech company, and then the sections that are more interior or intimate are acoustic. The singers change singing styles. Dorothy [performed by Blythe Gaissert] sings classical through the whole thing, but everyone else has a moment where they break into some kind of pop style.

Jason: And does the piano represent “Sam the piano player” in Casablanca?

Kamala: I did think about the piano in Casablanca, but I don’t know that I thought they were one-to-one

Jason: How did your thinking evolve over the years you two have been working on this?

Kamala: The changes in the news have driven a lot of revisions. When we started out, it was 2013, and Snowden had just released his big document dump. It was all very new. We were in a writer’s group, and we came up with a couple songs. And as we kept going, more things kept happening, and then the election, and Cambridge Analytica. All of that had to make its way into the piece.

Jason: Since the character in your story, Ethan Snyder, is a reference to Edward Snowden, I’m wondering what you think about Snowden? Initially many people thought of him as a hero but now they associate him with Putin and the forces that helped get Trump elected.

Rob: It’s complicated. One of the great things that happened with this show over time is shifting away from Assange and Snowden—who I felt were really interesting when they first emerged because they believed that they were in a glamorous spy movie.

But what we’ve become interested in since then is more about the architecture of this spy web than the people exposing it. Books like Twitter and Tear Gas by Tufecki and Surveillance Capitalism contributed to our looking at the big picture and what it means for individuals and their ability to protest, or take on their governments. And the threat that’s posed to that has really become the main character of the show.

Another way we avoided some of the problematic aspects of these real-life characters is by gender reversing Casablanca, so that the Snowden character is really Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca, and our protagonist, Dorothy, is Humphrey Bogart and is the one faced with the moral choice.

Jason: Oh wow! I was wondering about that because Casablanca is more about the triangle relationship between those two characters and Bergman’s character’s boyfriend, which I didn’t see when I read your libretto.

Kamala: An early draft of the piece had a triangle relationship, but we realized we weren’t really interested in that, and we got rid of it.

Jason: Do you think privacy is important in itself, or is it just problematic when people’s personal data gets exploited, like it did in the 2016 election to help Trump get elected?

Kamala: I think you bring up an interesting philosophical question. What does privacy even mean in this day and age, and why should we care about it? That has come up a few times, especially from people who are younger and don’t really have the same ideas about privacy that we have. But I think everyone still wants a space where they can express themselves freely and not be thrown in jail because of it. We should not be empowering governments or companies to know so much about us that they can make decisions about us based on what they think we’re going to do because of what we have done before. That’s already where we’re headed.

Jason: That theme is kind of Luddite, but the show uses technology in real time in an exciting way. At first I wondered if that was a contradiction, but I’ve come to think that the data mining that happens is more a tremendous example of theater magic than it is about using new technology.

Rob: I think you’re definitely onto something. When we tried it out in our various test runs, it really made me aware of how it’s making a group of people who come together in a room look at themselves and who they are, and be aware that they’re in a space with other people. Just like we’re in a space with other people on earth, or in a space with other people in a country. But we don’t actually have to see those people. When we go on Facebook, we don’t actually see those people. We don’t see the people who are sending us messages that are disturbing. And being in a room with someone is different than seeing them in the internet. Being aware that someone in the room would say something on social media that you wouldn’t say to someone across the table. That has been exposed in the workshops for the show.

Kamala: That’s why the piece isn’t really Luddite, because I don’t think we’re saying you should not post on social media, just that you should be aware of what’s being done with your data and who can see your posts. But because the tech companies are making so much money, we cannot trust them to act in a way that isn’t harmful towards their customers. Because there are no regulations in place to force tech companies to be careful with your data, they can do whatever they want with it. And until people care enough to harass their congressmen to change laws, it’s going to be on the person to take care of themselves. You’re not safe online, and you should be. So what are you going to do about it? The problem with something like this is because it’s such an abstract thing, the policy is so complicated, a lot of people just don’t even think about it.

Jason: In real life, I put my foot in my mouth pretty often, but on social media, I tend to be pretty careful about what I say. But when I went to the workshop performance some of my posts popped up on the screens and it felt weird because they didn’t have their original context. So that was eye opening for me.

Rob: As the show emphasizes dramatically, it comes back to the fact that your data is not distributed by people; it’s distributed by computer programs. There’s a place on Facebook where you can go and see what Facebook has concluded about you which helps guide advertisements toward your profile. And so when we were working on the show, many of us went on Facebook and looked at that feed. Anyone can look at it. It’s public. It’s interesting to see the things this algorithm was correct, and incorrect about.

I keep getting ads now on Twitter from an astroturfing group. It’s a clearly fake “grassroots” group called Airbnb Citizen, where they want me to contact my city councilmen and tell them to defend the rights of people to use Airbnb and rent out their apartment. And the reason I was so struck by the fact that I’ve only been getting this for the last two weeks is that the algorithm thinks I live in Jersey City where we’re rehearsing the show, whereas actually I live in Pittsburgh. It’s just getting it from my GPS.

Jason: That’s pretty creepy. But I was also wondering about your approach to libretto writing and how it differs from your playwriting? Your libretto tends to be pretty spare. It’s not wordy. And I notice you use an ABCB rhyme scheme a lot.

Rob: It’s not really required to use rhyme, but I just got carried away. The great thing about writing opera librettos is the idea to use as few words as possible, and it’s all about taking words away as you go through the process. I find that really daunting and really delightful.

Jason: As you revised, the language became starker?

Rob: I think in some places, especially the big arias, which is where you want to say the most with the fewest words.

Jason: Do you think of Looking At You as an opera, or are you avoiding the word “opera” for any reason?

Kamala: HERE has a relationship with more theater reviewers, and we wanted them to be the ones to come rather than just the classical music people.

Rob: It really is a hybrid piece in so many ways, both theatrically and musically.

Jason: For some opera purists, the EDM—and probably other aspects—would make them think it’s not opera.

Kamala: Exactly.

Jason: I’m not a purist, so for me, it’s clearly opera.

Kamala: I think it’s an opera. But, it’s also about trying to get people who haven’t been to an opera before to come.

Jason: Lots of people are afraid of opera. They’re probably more afraid of opera than they are of their data being exploited.

Kamala: Yeah, I think that’s true.

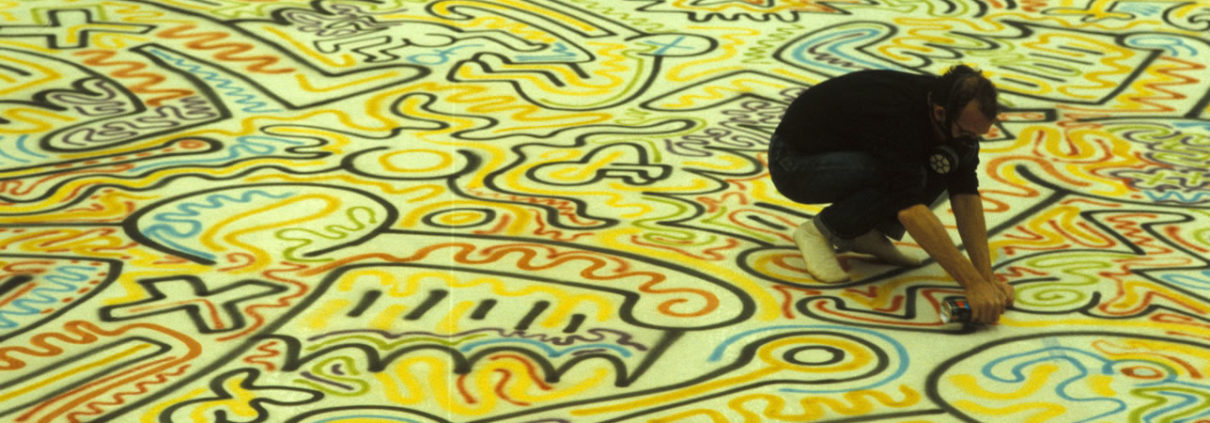

Opera traditionally had a significant niche in society. Elements of grandeur and allure have made it enjoyable for many. For some, however, it resembles a sophistication and timelessness that can be foreign. Conceptualizing a design that pays homage to the mysticism of the art form while presenting the work in a contemporary, easily digestible format was a challenge. The task lead me down paths I hadn’t explored before and took tolls on my process. When it was all on my drafting table there were two distinct themes that stood out for Flash Operas: the history associated to a grande drape coupled with a continuity in aesthetics. In actuality this project involves six distinct stories in a short matter of time. So in theory it requires six different designs. With my concepts I envisioned the space as a canvas and I wanted the stories to illuminate that canvas.

Opera traditionally had a significant niche in society. Elements of grandeur and allure have made it enjoyable for many. For some, however, it resembles a sophistication and timelessness that can be foreign. Conceptualizing a design that pays homage to the mysticism of the art form while presenting the work in a contemporary, easily digestible format was a challenge. The task lead me down paths I hadn’t explored before and took tolls on my process. When it was all on my drafting table there were two distinct themes that stood out for Flash Operas: the history associated to a grande drape coupled with a continuity in aesthetics. In actuality this project involves six distinct stories in a short matter of time. So in theory it requires six different designs. With my concepts I envisioned the space as a canvas and I wanted the stories to illuminate that canvas.