EiO Artistic Director Jason Cady interviewed Flash Opera composer Miguel Frasconi about his early development as an experimental music innovator and about his approach to adapting ‘Things You Should Know’ by AM Homes for the opera stage.

CADY: I wanted to start off with your background. I know you’ve worked with a lot of important artists like John Cage, Morton Subotnick, Joan La Barbara, and Jon Hassell.

FRASCONI: Yeah, well one name that you didn’t mention was Jim Tenney who I studied composition with up in Toronto. Jim and I worked a lot together and were really close, so he was huge influence on me.

CADY: And your father Antonio was an artist; you told me earlier that he was friends with Gerry Mulligan and Earle Brown.

FRASCONI: Yeah, I grew up in a creative household. Both my parents were visual artists, my dad was a pretty well-known woodcut artist and my mom, Leona Pierce, was also a well-known woodcut artist, but, as women did in the ‘50s, she gave up her creative work in order to make her household and family her creative work. When I was growing up every weekend was a dinner party with different people coming over like Nat Hentoff and Pete Seeger. They knew those people quite well from Greenwich Village which is where I was born.

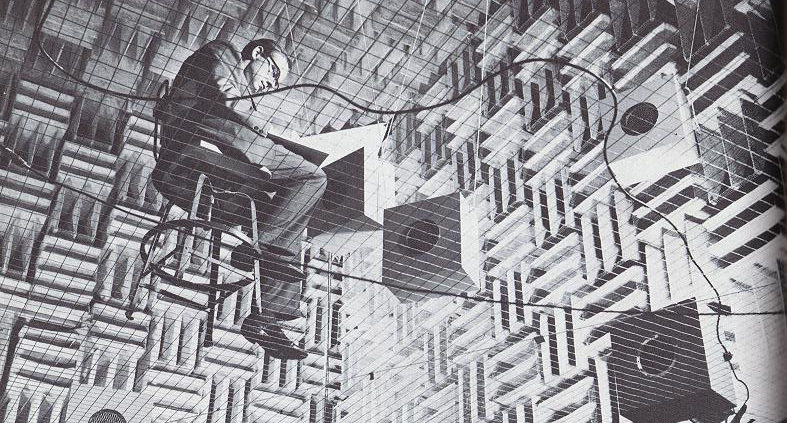

from “On the Slain Collegians.” 1970. Antonio Frasconi.

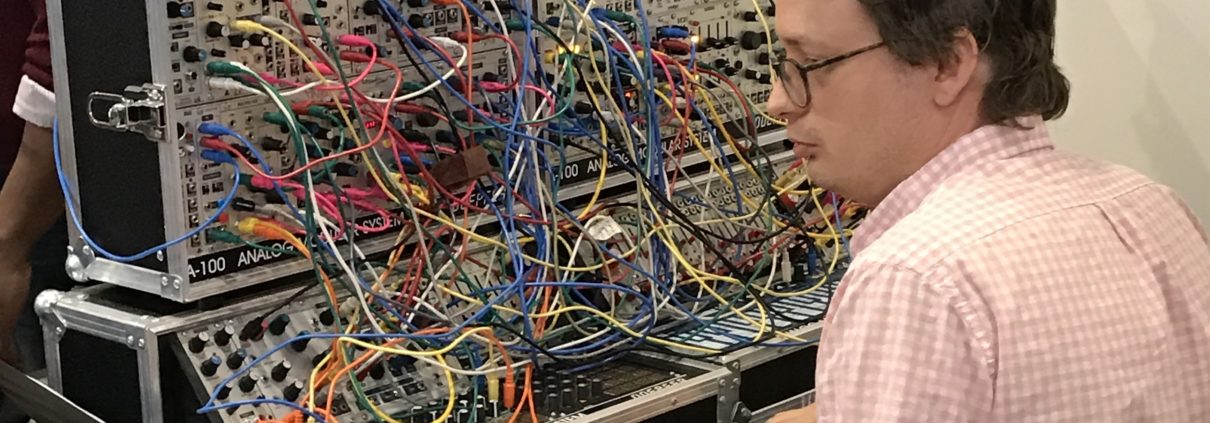

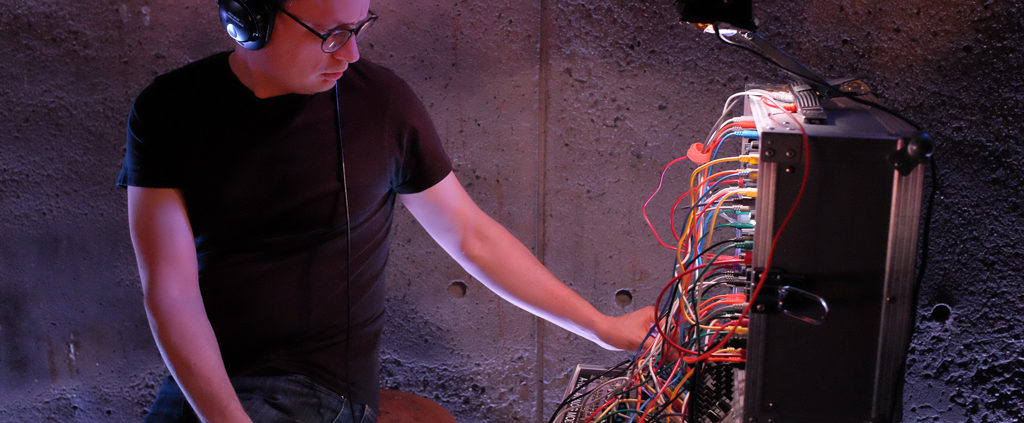

CADY: Also, part of your background are all these interesting instruments you play. I know you play glass instruments, the Buchla modular synthesizer, piano, and also various world music instruments like mbira and gamelan.

FRASCONI: In high school I was a sort of sound freak. Living so close to New York when I was young, my dad would take me to all these great concerts. There was one really amazing series by the Juilliard Contemporary Music Ensemble that was at that time lead by Dennis Russell Davies called “New and Newer Music.” I went religiously. That’s where I heard my first Feldman, my first Cage, and my first Stockhausen during the American premiere of Stimmung. It was really quite amazing.

In the ‘60s there was this sort of antiestablishment, anti-history, anti-academia bent going on so I wanted to find creative work that was uniquely twentieth century. At the time, what people called “new music,” particularly electronic music, was uniquely twentieth century. My brother was a filmmaker and one thing he said was that he liked film because it was a uniquely twentieth century art form. I looked for music that was uniquely twentieth century and electronic music was that. I never thought of myself as a classical musician. Well, I did, but one who ignored anything before Ives and Satie.

I decided to be a composer when I was around eight or nine. My school took a field trip to the Norwalk symphony and they played Charles Ives’ Third Symphony. I had never really felt close to music, but when I heard this symphony it didn’t sound like any music I had ever heard; the only thing my young brain could equate it to was weather. I grew up in a house with a lot of windows, with trees all around, and when there was a storm you really felt like you were in the middle of it. That’s what that Ives symphony felt to me, like being in the middle of a storm. I thought “if a human being can create that sort of thing, that’s what I wanna do.” I didn’t want to create music. I wanted to create something on the elemental level of weather.

Then, when I was in high school, Fred Hellerman of The Weavers was over for dinner. In the middle of dinner, I heard this ethereal sound that seemed to be coming from the walls. I looked over and saw Fred with a smile on his face, his finger on the edge of a wine glass. It just blew my mind because I had never seen that done before. The next day I took all my parents’ stemware down to the basement and made my first glass instrument and I’ve been playing glass ever since. When I went to York University in Toronto to study electronic music with David Rosenboom and Richard Teitelbaum, I discovered that there were a bunch of students who were using glass as a sound source for electronic music. After a couple years of that, I thought, “Why don’t we get together and make electronic music without any electricity?” We started this group called the Glass Orchestra in 1977, which was a quartet I was in for ten years.

Miguel Frasconi playing some of his glass instruments.

CADY: How many glass instruments were there? I assume this was not just the Benjamin Franklin glass harmonica.

FRASCONI: I always thought the objective in this group was to create a complete world music culture. There were wind instruments, percussion instruments, a whole range of instruments, but all made of glass. Before Franklin came up with the glass harmonica there was the glass harp, which was basically basically a table with a bunch of stemware on it. So we each had one of those. We would use duck calls in tubes that would create all sorts of wonderful harmonics. You’d play it vertically, blowing the tube up and you’d get all the different harmonics as the duck calls travelled up and down the tube. One of the guys in the group called it the puke-a-phone. So basically, anything made of glass was fair game, and that’s still the way I approach my glass instruments. After forty-some years I have a lot of broken glass instruments which sound amazing: rich and full of harmonics and unexpected sound. I still use glass as a totally exploratory mode.

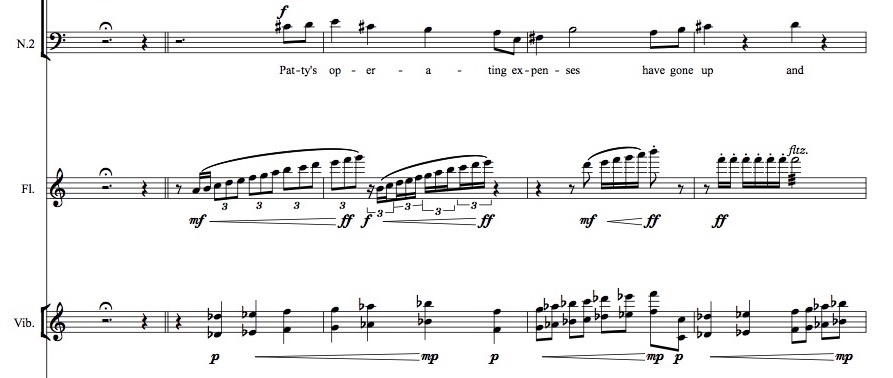

CADY: Getting to your opera now [*], there seem to be two possible interpretations of the story: number one, that it’s a light and funny story, or number two, that it’s a dark story and it’s more Kafkaesque or like Samuel Beckett. Yet I think you’ve chosen a third interpretation: that it is an experimental process music kind of story. Do you find the other interpretations relevant?

FRASCONI: I found it not quite Kafkaesque but definitely Beckett-esque. This story is about a fellow who thinks there’s a list or there might be a list and he doesn’t know what’s on it. So, I wanted to create a situation where the audience will be put in a position to somehow start making their own lists about what they’re experiencing. I’ve written a few operas and I thought this is an opportunity to create an opera that has more to do with what I’m personally interested in, which is I like to create music that is not so much presentational as it is experiential.

Marbles. 1955. Leona Pierce.

CADY: The story resonated with me because I often feel like I was not there the day when the list of rules was given out. Do you personally relate to it?

FRASCONI: Oh, absolutely. The first minute is basically just people singing, “There are things I don’t know” over and over again. It felt so cathartic. At this point in my life, I have no idea what will happen.

CADY: I remember you said your piece turned out really weird. Is this opera atypical of your work? Or did it just turn out in an unexpected way?

FRASCONI: I took the same approach with this opera as I do when I play glass instruments. If I’m doing something and I know what it’s going to sound like, it’s not terribly interesting to me. I need to discover something that’s new to me. That’s the approach I took with this opera. There are these first two and a half minutes where it’s pretty static and repetitive and then it quickly switches into a totally different gear. That’s the sort of thing that attracts me to experimental music: you never know what’s gonna happen.

CADY: You perform a little bit in this opera. I’ve been thinking about how being a composer/performer is part of what Experimental Music is because it’s about having a vision that’s so unique that the composer has to be involved in the realization of the music.

FRASCONI: For me it isn’t so much about the composer being the performer but the performer making compositional choices. The composition itself allows for the performers’ predilections to come in, so it makes sense that in experimental music the composer is also a performer. Experimental music keeps the door open for performers to be more active.