Outcome to Show Them

As an artist, I often bristle at the idea of an outcome. My work as a composer is the outcome. That musicians have music on their stands and the resulting sounds were as I intended is the outcome. For a painter an outcome might be a painting. For a writer, poem.

But for another segment of our artsosphere (the system of institutions, funders, presenters, etc.) the idea of an outcome is much more nuanced and varied. Outcomes are a part of most grant applications and often come up when talking to donors. Governments and board members also really want to know what came out of your work as an artist. Instead of just music on a stand and the sounds in the ears of the audience, let’s take a moment and think about what else is impacted by this supposedly simple act.

For one, I am impacted as the artist who made the work. It may have taken me months to make that work, during which time everything in my life was at least tangentially related to the work. From the food I ate, the books I read and the conversations I had with friends and peers, my work on the new piece changed things. In an overly dramatic way, my life will never be the same.

How about the musicians themselves (and as an opera composer I mean both those musicians in the pit and on the stage), how have they been impacted on by this new set of markings on paper? Chances are, the new piece relates somehow to the music they have read or acted before. But there may be instances where they need to use their imagination to connect more deeply to new material that has no precedent. The musicians are being asked to grow into the new music and alongside it, entering into a dialogue with it. This too changes them. It affects their aesthetic sensibilities (for good or bad), and may even impact on their physical facility with their instruments.

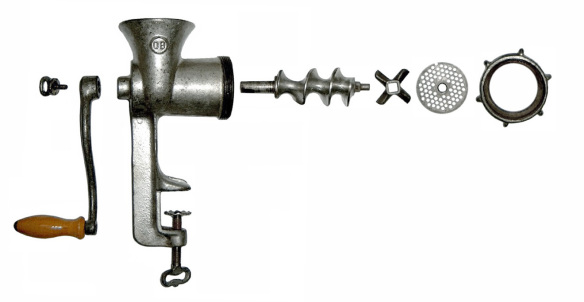

The audience has less of a sustained experience with the work, but seeing it after all the work is done sustains the audience’s experience of the work as miraculous. The experience of awe is something that the musicians and composer most likely are unable to have with a piece they have sweated so intensely over. (Isn’t it always better to just eat the sausage without seeing it stuffed?). The audience then can be shocked into a heightened state by the brief engagement with the work. The audience might also be more likely to talk with others about the work (water coolers anyone?) thereby creating a ripple effect within a larger community. This is representative of another iteration of the work, this time filtered through a more personal lens.

The outcomes of these impacts together are an ecosystem of engagement, personal and cultural adjustments to novel presentations, and a ‘making of room’ within communities for new voices to dictate the topics, tone, duration and ideas of their story.

One other thing of note to this discussion is the question of duration and its meaning to the projected outcomes. It is fairly safe to say that most of the impacts described above are fleeting and easily replaced by whatever next occupies the energy and imagination of the involved parties. Much of the research about impact says that real change is not so much a result of programs or in this case the art being made. Instead, the sustainable change comes from the relationships built around the art work. This approach emphasizes further the need for composers to stay with their musicians and audiences for prolonged periods of engagement and re-engagement to make the kind of impact that that we all want to make in the world. We make art to create and reflect on meaningful experiences, ideas and stories. We should recognize the potential that this work has to be part of our collective world in lasting ways.

– Aaron Siegel